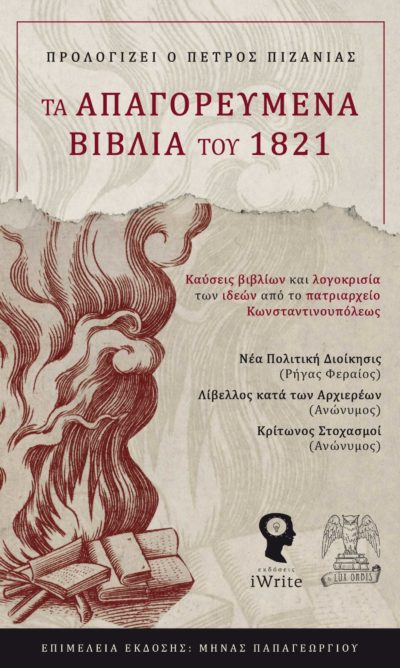

Από τον πρόλογο του συγγραφέα Πέτρου Πιζάνια, από το βιβλίο «Τα απαγορευμένα βιβλία του 1821»

Οι πρώτοι Έλληνες πολιτικά ριζοσπάστες διαφωτιστές εμφανίστηκαν πριν από τη Γαλλική Επανάσταση στις αρχές της δεκαετίας του 1780. Πιστεύω πως στους προδρόμους αυτών των Ελλήνων επαναστατών διανοουμένων πρέπει να εντάξουμε τον Ιώσηπο Μοισιόδακα, χάρη στο έργο του Περί παίδων αγωγής που εκδόθηκε στη Βιέννη το 1779, και ιδίως χάρη στην Απολογία του 1780.

Στην ίδια κατηγορία πρέπει να εντάξουμε και τον Ανώνυμο του 1789, και φυσικά τον Ρήγα Φεραίο με το Σχολείον των Ντελικάτων Εραστών. Όσοι δημόσια, με κάποια έκδοση, δήλωσαν τη στροφή τους προς ανατρεπτικές επιλογές, ήταν ασφαλώς λίγοι, μας επιτρέπουν ωστόσο να υποθέσουμε πως υπήρχαν περισσότεροι που σιωπούσαν ή απλώς δεν τους γνωρίζουμε – αυτός είναι πάντα ο κανόνας.

Πρωτοπόρος της πολιτικής επαναστατικής δράσης σε όλα τα Βαλκάνια ήταν ο Ρήγας Βελεστινλής. Θα τον περιβάλλουν αρχικά και θα ακολουθήσουν το παράδειγμά του στη συνέχεια και άλλοι διανοούμενοι, έως τη συμμετοχή πολλών από αυτούς στη Φιλική Εταιρεία στην οποία αντιπροσώπευαν λίγο πριν την Επανάσταση του 1821 το 17% του συνόλου των γνωστών μελών.

Οι επαναστάσεις μετά τη Βαστίλη

Η Γαλλική Επανάσταση ως παράδειγμα θα προτρέψει στην πολιτική επαναστατική δράση πολλούς διανοουμένους σε όλη την Ευρώπη μεταξύ αυτών τον Ρήγα και τους συντρόφους του.

Το κατεξοχήν χαρακτηριστικό γνώρισμα κάθε επαναστάτη σε όλες τις ιστορικές περιόδους είναι η πολιτική πράξη και οι ιδεολογικές και θεωρητικές θεμελιώσεις των αξιών και των στόχων, όπως εκφράζονται σε κείμενα. Το ίδιο ίσχυε και για τους Έλληνες διαφωτιστές επαναστάτες. Ο Ρήγας Βελεστινλής, πρώτος αυτός, εισήγαγε τον ελληνικό επαναστατικό Διαφωτισμό στο πεδίο της πολιτικής πράξης, και αυτό τον καθιστά επικεφαλής των πρωτοπόρων σε όλα τα Βαλκάνια.

Όλο το έργο του δεν είχε δημιουργηθεί για να συμβάλει στη θεμελιώδη γνώση, αλλά ήταν λόγος με αποκλειστικό προορισμό να στηρίζει και να προωθεί την πολιτική πράξη για την ελευθερία. Το κείμενο του Ρήγα για τη Νέα Πολιτική Διοίκηση που δημοσιεύεται στον παρόντα τόμο τον συνδέει με τον Ζ. Ζ. Ρουσώ και τη Γαλλική Επανάσταση.

Συγκεκριμένα πρόκειται για μια προσαρμογή του Συντάγματος που συνέταξε η γαλλική Συμβατική Εθνοσυνέλευση τον Ιούνιο του 1793 υπό την κυριαρχία των Ιακωβίνων.

Το Σύνταγμα αυτό, παρότι δεν εφαρμόστηκε στη Γαλλία, ενέπνευσε πολλούς επαναστάτες και για πολλά χρόνια κυρίως επειδή κατοχύρωνε στο νομικό επίπεδο το πολίτευμα που είχε γίνει σταδιακά πράξη από τον Αύγουστο του 1792 και μετά την εκτέλεση του Γάλλου βασιλιά.

Πρόκειται για το Λαϊκό Πολίτευμα (République) αυτό που οι συνταγματολόγοι αποκαλούν αρκετά αμήχανα αβασίλευτη δημοκρατία. Ο διαφωτιστικός ριζοσπαστισμός του Συντάγματος αυτού εκφράζεται ρητά στο πρώτο άρθρο ήδη από την αρχική πρόταση: Ο σκοπός της κοινωνίας είναι η κοινή ευτυχία.

Οι πρωτοβουλίες του Ρήγα

Η τεράστια δύναμη την οποία εξέπεμπε η Γαλλική Επανάσταση παρωθούσε στον σχηματισμό μιας άτυπης Διεθνούς ιδεολόγων, οργανώσεων και οπαδών σε όλη την ευρωπαϊκή ήπειρο και εν μέρει την αμερικανική. Ένας από τους πρώτους που το αντιλήφθηκαν και αυτοβούλως προσχώρησαν ιδεολογικά ήταν ο Ρήγας Φεραίος.

Ο Ρήγας, αντισκοταδιστής, αντιοθωμανός, μαχητής της ελευθερίας ήδη πριν το 1789, συνέλαβε τη μεγάλη σημασία της οργανωμένης πολιτικής δράσης και της ιδεολογικής υποκίνησης. Και για τούτο, προφανώς, συγκρότησε τη δική του επαναστατική οργάνωση και ξεκίνησε την πολιτική διαφωτιστική του δραστηριότητα. Η Νέα Πολιτική Διοίκηση την οποία πρόλαβε να δημοσιεύσει το 1797, αποτελούσε, συνεπώς, ένα πολιτικό και ιδεολογικό μανιφέστο, ένα σχέδιο για το πολιτικό μέλλον των βαλκανικών λαών.

Ο Ρήγας σχεδίαζε κάτι μεταξύ μια κοινοπολιτείας και μιας μικρής πολυεθνικής δημοκρατίας στα όρια των Βαλκανίων που θα περιλάμβανε όλους τους αντίστοιχους πληθυσμούς. Εισήγαγε, όπως μπορεί να αντιληφθεί ο παρατηρητικός αναγνώστης, τη Λαϊκή κυριαρχία (άρθρα 25ο και 26ο) την οποία ακόμη τότε ο Ρήγας αποκαλεί «αυτοκρατορία» εννοώντας, όπως προκύπτει από τα συμφραζόμενα, τη λαϊκή πολιτική αυτεξουσιότητα.

Το δεύτερο σκέλος της στρατηγικής του Ρήγα, διάχυτο στο έργο του, ήταν αμιγώς πολιτικό. Αφορούσε τη συμμαχία με το ισχυρό κράτος εκείνο το οποίο θα στήριζε μια παρόμοια στρατηγική για τα Βαλκάνια. Ήταν εύλογο τότε να περιλαμβάνει στην πολιτική του σκέψη την αναζήτηση μίας συμμαχίας με ισχυρό ευρωπαϊκό κράτος, είτε διαβλέποντας προς τον πάγιο εχθρό της Οθωμανικής Αυτοκρατορίας, τη Ρωσία, είτε στους αναδυόμενους απελευθερωτές των ευρωπαϊκών λαών, στους Γάλλους επαναστάτες, οι οποίοι άλλωστε είχαν προωθηθεί έως τα Επτάνησα το 1797.

Ο Διαφωτισμός των Ελλήνων

Η στρατηγική απελευθέρωσης όλων των βαλκανικών λαών από την οθωμανική κυριαρχία, όπως την είχε συλλάβει και επιδίωκε να την εφαρμόσει ο Ρήγας, ξεπεράστηκε γρήγορα από τις ιστορικές εξελίξεις. Σε μία εποχή που γαλλικά στρατεύματα ξεκινούσαν ακόμη και τις μάχες με την ιαχή «Ζήτω το έθνος», η πολυεθνική πολιτεία του Ρήγα ξεπεράστηκε πολύ γρήγορα.

Πρώτος ήταν ο Αδαμάντιος Κοραής ο οποίος εθνικοποίησε το σχέδιο για την ελευθερία. Μόνο οι Έλληνες έχουν τις ιστορικές, οικονομικές και πολιτισμικές προϋποθέσεις να κερδίσουν την ελευθερία τους, υποστήριξε το 1803. Αλλά για τούτο πρέπει όχι απλώς να ταυτιστούν, ακόμη περισσότερο να ενταχθούν οργανικά στα στρατεύματα του Ναπολέοντα. Ο Κοραής είχε απορρίψει τον πολυεθνικό χαρακτήρα της βαλκανικής δημοκρατίας του Ρήγα αλλά διατήρησε το ζήτημα των διεθνών συμμαχιών.

Οι Έλληνες δεν μπορούσαν παρά να συμμαχήσουν με μια μεγάλη δύναμη για να στηρίξουν την απελευθέρωσή τους – αν δεν τους απελευθέρωνε κιόλας από μόνη της. Και η επαναστατική Γαλλία ήταν για τον Κοραή, όχι απλώς μια συγκυριακή επιλογή αλλά η μόνη υφιστάμενη στρατηγική επιλογή για τους Έλληνες.

Ωστόσο, το κλειδί της διαμόρφωσης της πολιτικής στρατηγικής για την ελευθερία των Ελλήνων που υιοθετήθηκε και κατά την Επανάσταση του 1821, το συνέλαβε ο Ανώνυμος συντάκτης της Ελληνικής Νομαρχίας.

Με το βιβλίο του προέτρεπε τους Έλληνες να στηριχθούν στις δικές τους δυνάμεις, και υπό αυτή την οπτική κατονόμαζε, έκρινε και καταμετρούσε τις κοινωνικές δυνάμεις που θα μπορούσαν να σηκώσουν την Επανάσταση του 1821. Στους αντίποδες της ελευθερίας των Ελλήνων τοποθετούσε τον ορθόδοξο κλήρο του Πατριαρχείου όπως και τους Φαναριώτες τους οποίους θεωρούσε «συνεργούς της τυραννίας» προς ίδιον όφελος.

Ειδικότερα τους αξιωματούχους του κλήρου τους όριζε ως «αμαθές […] και διεφθαρμένον ιερατείον». Έτσι, ο Ανώνυμος με την Ελληνική Νομαρχία αποτέλεσε στο πλαίσιο του Ελληνικού Διαφωτισμού το πλέον συγκροτημένο θεμέλιο τόσο της πολιτικής στρατηγικής για την ελευθερία όσο και της κοινωνικής κριτικής προς τις ποικίλες ομάδες ισχύος αλλά και του πληθυσμού των ταπεινών Νέων Ελλήνων.

Ο άγνωστος (μέχρι σήμερα) Λίβελλος

Τα κείμενα που συντάσσονταν ή μεταφράζονταν από Έλληνες διανοουμένους στην Επανάσταση μετά τη Νομαρχία επικεντρώνονταν στην ιδεολογική και κοινωνική κριτική και την καλλιέργεια της σκέψης, όλα με την οπτική του αγαθού της ελευθερίας.

Ένα σημαντικό παράδειγμα αποτελεί ο Λίβελλος κατά των Αρχιερέων που κυκλοφόρησε χειρόγραφο το 1810 από ανώνυμο συγγραφέα και έκτοτε δημοσιεύεται στο σύνολό του για πρώτη φορά στο βιβλίο “Τα απαγορεύμενα βιβλία του 1821” (εκδ. Iwrite – Σειρά Lux Orbis). Αυτό το κείμενο, παρότι χειρόγραφο, θα πρέπει να είχε ευρεία διάδοση, και για εμάς σήμερα είναι πολύτιμο για πολλούς λόγους. Ο πρώτος είναι ότι συντάχθηκε στο πυρήνα του πνεύματος του Διαφωτισμού, ελληνικού και ευρωπαϊκού.

Γράφει εισαγωγικά: «Δύο μεγάλα καί φοβερά κακά ἐπροξένησαν πάντοτε τήν δυστυχίαν τοῦ ἀνθρωπίνου γένους, η Ἁμάθια και ἡ Δεισιδαιμονία. Και η πηγή αυτών των δύο κακών είναι κοινωνική και ο συγγραφέας την κατονομάζει: Ἡ σκληροτέρα μάστηξ τοῦ Γένους {των Ελλήνων} εἰσίν οἱ Αρχιερεῖς». Ο ανώνυμος συντάκτης του Λιβέλλου αποδεικνύεται από το κείμενό του αμετακίνητος ορθολογιστής.

Περιγράφει συγκροτημένα και με εξαιρετική γνώση τις πρακτικές θησαυρισμού των ορθόδοξων κληρικών αξιωματούχων σε βάρος των ελληνικών πληθυσμών κατά τη διάρκεια της οθωμανικής κυριαρχίας. Αυτές οι πρακτικές είχαν, ακριβώς, ως προϋπόθεση την αμάθεια και τη δεισιδαιμονία και ασφαλώς τον φόβο τόσο για τα μετά θάνατο πράγματα όπως πίστευαν, όσο όμως φόβο και για τα επίγεια. Φόβο για τα επίγεια για τον απλό λόγο ότι η ορθόδοξη κληρική αριστοκρατία ήταν ενσωματωμένη οργανικά και αντιπροσώπευε το οθωμανικό κράτος. Ασκούσε, συνεπώς μια διπλή εξουσία όπως είπαμε, τόσο στο όνομα των κατακτητών όσο και στο όνομα της πίστης. Και αυτές χρησιμοποιούσε ως μέσα ισχύος για ίδιον όφελος όσο και για επιβολή της υποτέλειας την οποία πρόβαλε ως τιμωρία προερχόμενη από τον Θεό.

Αυτά τα ζητήματα τα οποία πολύ συνοπτικά αναφέρω εδώ έχουν λυθεί από την επιστημονική έρευνα. Αλλά ο ανώνυμος συγγραφέας στην εποχή που συνέτασσε τον Λίβελλο κατείχε εξαιρετικά εμπεριστατωμένη γνώση των μηχανισμών δράσης, εκμαυλισμού και εκμετάλλευσης που ασκούσε η πλειονότητα των αξιωματούχων του ορθόδοξου κλήρου στο ποίμνιο τους, από τον βαθμό του αρχιμανδρίτη έως εκείνον του μητροπολίτη, ακολούθως της Ιεράς Συνόδου του Ορθόδοξου Οικουμενικού Πατριαρχείου.

Ωστόσο, γνωρίζουμε ότι από αυτές τις λίγες εκατοντάδες αξιωματούχους του ορθόδοξου κλήρου θα ξεχωρίσουν ελάχιστοι, τριάντα περίπου, αλλά σημαντικοί οι οποίοι ήταν ήδη οργανωμένοι στη Φιλική Εταιρεία. Αναφέρομαι στους μαχητές στην Επανάσταση του 1821 όπως ο Επίσκοπος των Παλαιών Πατρών Γερμανός, ο Επίσκοπος Σαλώνων Ησαΐας, ο Επίσκοπος Βρεσθένης Θεοδώρητος κ.ά.

Εννοείται αντικληρικαλιστές έναντι της τότε εκκλησίας, δηλαδή εναντίον του Ορθόδοξου Πατριαρχείου. Μάλιστα ο Παλαιών Πατρών Γερμανός, ο πλέον διαυγής και πολιτικά σημαίνον ιεράρχης, διατύπωσε λίγο πριν τον θάνατό του τον Μάιο του 1826, έπειτα από την Επανάσταση, την ίδια κριτική με τον συντάκτη του Λιβέλλου αλλά και με τον Ανώνυμο της Ελληνικής Νομαρχίας σχετικά με την πνευματική και μορφωτική κατάσταση του ορθόδοξου ιερατείου κατά την οθωμανική περίοδο.

Η προ Λίβελλου εποχή

Πριν και μετά τον Λίβελλο δημοσιεύτηκαν πολλές αυτοτελείς εκδόσεις κειμένων αλλά και πολλά άρθρα στα περιοδικά του ελληνικού διαφωτισμού. Ενδεικτικά ένα κείμενο κάπως αγνοημένο από την ιστοριογραφία. Κυκλοφόρησε το 1817 και επρόκειτο για ένα απλό, πρωτότυπο και μαχητικό μανιφέστο που ανέλυε την επαναστατική ιδεολογία της εποχής, με τίτλο Δοκίμιον περί Πατριωτισμού.

Πρόκειται για ένα βιβλίο εξήντα τεσσάρων σελίδων, όπου αναλύεται ο πατριωτισμός ως η επαναστατική ιδεολογία της εποχής από το πρίσμα των Ελλήνων. Έναν χρόνο αργότερα, εκδόθηκε για πρώτη φορά στα ελληνικά ένα από τα θεμελιώδη φιλοσοφικά έργα του ευρωπαϊκού Διαφωτισμού, συγκεκριμένα το βιβλίο του Ρουσώ για τις Απαρχές και τα θεμέλια της ανισότητας μεταξύ των ανθρώπων, μεταφρασμένο από τον Φιλικό Σπυρίδωνα Ν. Βαλέτα με ψευδώνυμο.

Και το 1819 εκδόθηκε στο Παρίσι ένα άλλο πολύ σημαντικό πρωτότυπο ελληνικό φυλλάδιο με τίτλο Στοχασμοί του Κρίτωνος. Πρόκειται για το τρίτο κείμενο του παρόντος τόμου. Οι Στοχασμοί αναφέρονται στα ζητήματα της εκπαίδευσης και ευρύτερα της μόρφωσης, ζητήματα τα οποία βρίσκονταν διαρκώς και με ένταση στην καρδιά της δράσης των Ελλήνων διαφωτιστών διανοουμένων.

«Ὁ χαμὸς τῆς ἀληθινῆς μαθήσεως, δηλαδὴ τῆς φρονήσεως καὶ ἠθικῆς, φέρνει, καθὼς τῶν ἰδιωτῶν, ἔτζι καὶ τῶν ἐθνῶν, τὴν καταστροφήν. […] ἡ ἔλλειψις τοῦ πατριωτισμοῦ, ὁ ζῆλος δηλαδὴ τοῦ κοινοῦ συμφέροντος, ὁ ὁποῖος, τέκνον εὐγενὲς τῆς ἐλευθερίας, φεύγει ὅταν ἡμέραι δουλικαὶ ἠμαύρωσαν τὴν πατρίδα, καὶ ἀφίνει τὰς καρδίας εἰς μόνον τὸ πάθος τοῦ προσωπικοῦ συμφέροντος, πάθος καὶ γνώρισμα τῶν ἀγρίων».

Ο συντάκτης του κειμένου αυτού, αντικληρικαλιστής, ριζοσπάστης νεωτεριστής βρίσκεται σε αντιπαράθεση με την ορθόδοξη μητρόπολη της Αδριανούπολης επειδή σπαταλούσε τεράστια ποσά σε έργα προβολής και πολιτικής εδραίωσης αλλά σχεδόν τίποτε σε έργα μόρφωσης. Και προτείνει μια καινοτόμα, τότε, μέθοδο διδασκαλίας των κοινών γραμμάτων, μέθοδος η οποία όντως θα μπορούσε και ονειρευόταν να εφαρμοστεί μαζικά:

«…Τὸ μεγαλείτερον ὅμως καὶ δραστηριώτερον πρᾶγμα, […] ἤθελεν εἶναι ἡ εἰσαγωγὴ τῆς ἀλληλοδιδακτικῆς μεθόδου εἰς τὰ κοινὰ λεγόμενα σχολεῖά μας, ὅπου ὅλου τοῦ λαού τὰ τέκνα, καὶ ἑπομένως ὅλον τὸ ἔθνος εἰμπορεῖ εἰς ἓξ μῆνας νὰ μάθῃ νὰ γράφῃ, νὰ διαβάζῃ, νὰ λογαριάζῃ ὀρθά…»

Η γέννηση ενός νέου κόσμου

Οι Έλληνες διανοούμενοι του Διαφωτισμού, επαναστάτες και πολιτικά συντηρητικοί, δημιούργησαν τον δικό μας Διαφωτισμό, τον ελληνικό. Αυτοί αποτέλεσαν μια από τις κρίσιμες κοινωνικές ομάδες για την ανάπτυξη του Νέου Ελληνισμού.

Μορφοποιούσαν τον νέο κόσμο στο πεδίο της γνώσης και των ιδεών, άλλαζαν σταδιακά αλλά καταλυτικά τον μορφωτικό, ιδεολογικό, εν τέλει το συμβολικό φορτίο των μικρών νέων ελληνικών κόσμων. Κατά τη διάρκεια του 18ου αιώνα δημιούργησαν εντός της αυτοκρατορίας ένα σχετικά αυτοτελές πεδίο κοσμικής γνώσης και ιστορικής αυτοαναφοράς, μία μορφή η οποία αποτέλεσε προείκασμα της ελευθερίας των Ελλήνων. Αυτή η κοινωνική ομάδα των μορφωμένων επιστημόνων, δασκάλων, γιατρών, γραμματικών διαμορφώθηκε βαθμιαία από τα μέσα του 17ου αιώνα και ιδίως σε όλη τη διάρκεια του 18ου.

Ο λόγος για τον οποίο κατόρθωσε να έχει επίδραση ήταν ότι τα ίδια τα μέλη της προσδιόριζαν το περιεχόμενο των βιβλίων, της διδασκαλίας και εν γένει της δράσης τους, και μάλιστα παρά την εξάρτησή τους από τη χρηματοδότηση των εμπόρων. Με δυο λόγια, οι Έλληνες νεωτερικοί διανοούμενοι διατηρούσαν έντονη αυτοτέλεια στον καθορισμό των στόχων τους – για τούτο άλλωστε τους ορίζουμε εδώ ως διανοούμενους και όχι ως λογίους γενικώς. Μπορεί οι διανοούμενοι του είδους να μην ήταν πολλοί σε σύγκριση με ευρωπαϊκές κοινωνίες, μπορεί ακόμη να είχαν το μειονέκτημα ότι ξεκινούσαν από χαμηλές προϋποθέσεις για να δημιουργήσουν τα πάντα στηριζόμενοι στους υποστηρικτές και στις δικές τους δυνάμεις.

Επίσης, οι Έλληνες νεωτερικοί διανοούμενοι απευθύνονταν σε κοινωνίες με κλειστούς πνευματικούς πόρους, πολύ εντονότερα και αποπνικτικότερα θεοκρατικές σε σχέση με τις ευρωπαϊκές.

Ωστόσο, οι πνευματικές και ιδεολογικές τομές που προκάλεσαν σε τμήματα των βαλκανικών, ιδίως ελληνικών αστικών κοινωνιών ήταν τομές ιστορικά μη αναστρέψιμες. Σχολεία, βιβλία, διδασκαλία, συγκρούσεις ιδεών, ζητήματα της ελληνικής γλώσσας, κοινωνική κριτική διαμόρφωσαν χώρο για ελευθερία της σκέψης και της δημόσιας πολιτικής έκφρασής της. Ο σχηματισμός του Νέου Ελληνισμού και η Ελληνική Επανάσταση του 1821 δεν μπορούν να νοηθούν χωρίς αυτούς.

Σ’ ενδιαφέρει η Επανάσταση του 1821;

Βρες αυτό που ψάχνεις από τη σειρά Lux Orbis των Εκδόσεων iWrite